- How much and in what way did Bitef shape you up as contemporary dramaturge and author?

OLGA: Most definitely more than anything else in Serbian theatre. I have been following Bitef since the beginning of my studies.

MAJA: Bitef Festival has influenced my work since the beginning, probably more than anything else. Not only the festival but the theatre too. I have been following the festival since I can remember, and I think that it made a crucial influence on my work. I had an opportunity to participate in Bitef very early, with the Walking Theory performance Psychosis and Death of the Author, and I remember that that was the first time I felt I belonged somewhere. Just like some contemporary plays that have made an impact on my writing, so has Bitef influenced my poetics as an author.

- Can you remember when you started cooperating with Bitef Theatre and Bitef Festival?

MAJA: First time I worked at the festival as a volunteer was at my sophomore year, and after that I worked as a manager of guest troupes for years. That was a perfect way to see the performances and meet some artists that you learned about. I remember meeting Bob Wilson and watching the rehearsals of Woyzeck. Those are some unbelievable theatre experiences that I remember. From the magnificent feeling of watching that performance, to being in the position to see the other side of the coin and his way of running rehearsals, that I didn’t quite like. That was when I wondered why it should be necessary to base “great” art on (actor’s) fear, and (director’s) dominance, where the director is usually male. My first work in Bitef Theatre was also during my studies, when I worked as the dramaturge at the performance Belgrade Super Now by MONTAЖ$TROJ, and I think that I new right then that it would be my home away from home, that it would be the place where I would be able to make performances the way that I like.

OLGA: I was still a student - which means broke - and I applied to work over the summer and sort out the archives, footage of the festival performances, in return for the festival pass. That was my first cooperation.

- How different is the approach to work when you are only dramaturges from when you do auteur projects?

OLGA: My general feeling is like this: working on your own text is an individual, lonesome, long process which allow meandering, procrastination, and shaping your space and world with a different feeling of time flow. Auteur projects are a collective thing, they can exist without any responsibility towards the others, they are more focused, faster, more playful in a way. Both ways of work are charming in a way, and perfectly complement each other.

MAJA: I haven’t been working as a dramaturge on other people’s performances for a very long time. Somehow, it happened simultaneously that they stopped inviting me and I stopped finding myself in it. It may have happened because I turned to directing and auteur projects at some point, so dramaturgy felt a bit too narrow. On the other hand, working on text and auteur projects is radically different because, as Olga said, when you work on a text, you’re totally on your own, while when you work on an auteur project, text remains in symbiosis with other authors within the process. Both are very exciting, it’s just that the latter might feel less isolated.

- Your plays have often been performed in institutional theatres, but you also work a lot for the independent scene. Has your artistic practice linked to independent scene changed your approach to work in institutional theatre? Where do you reveal yourself more, where do you have more fun, where do you feel freer? How do you find a critical balance between working in institutions and your activism in theatre? Or are they inseparable?

OLGA: Those two types of work are complementary, because after working for independent scene, you can see the problems of institutions more clearly and vice versa. Therefore, since I have experienced both, I cannot romanticize artistic work anymore. Independent scene means insecurity, small fees, lack of space, and bureaucracy of constantly searching for fundings and explaining how you used it. Institution is somewhat rigid towards what you want to do and how you want to do it and has hierarchies that are stronger and more clearly organized. I think that our work, which is far from classical mainstream of Serbian theatre, will always fall into some liminal space between independent scene and institutions. And after all these years, maybe we are used to being somewhere in between.

MAJA: I also think that our work for institutional theatre resembles working on independent scene - from the way we approach the process (preparations, communication with the team, trying to avoid strict hierarchies) to how the performances eventually look like. I have never felt that our performances belong to theatre mainstream even when they were on big stages of some institutional theatres. I agree with Olga when she says that maybe we are used to being in between, neither institutionalized nor completely independent. That is what this performance is about in a way.

- You have been cooperating for years. You started some important projects that stood out by addressing some burning issues in our country and in the world. What kind of creative link brings you together and ignites your creative fire? And, since you do work together would you say that there is a unique approach, or does every project ask for a different approach, different methodology?

MAJA: Before we started working together, Olga and I were very close friends for years, and I think that it’s an important basis for a professional cooperation. We know each other very well, we know our strengths and weaknesses, and I think that it makes the process easier, especially when it enters the final, most stressful phase. I think that we are complementary, both in terms of characters and in terms of art. Although each performance is unique, there are some similarities in methodology. We always start with an idea, talk about it a lot, trying to realize what our approach and focus might be, then enter very long research, and then we create the text, which is usually based on improvisations. Both of our independent auteur projects (Freedom Is the Most Expensive Capitalist Word and World Without Women) were created through cooperation with Igor Koruga, choreographer, and Anja Đorđević, composer, without either of whom we cannot even think of that theatre adventure. They are always with us, through all the phases.

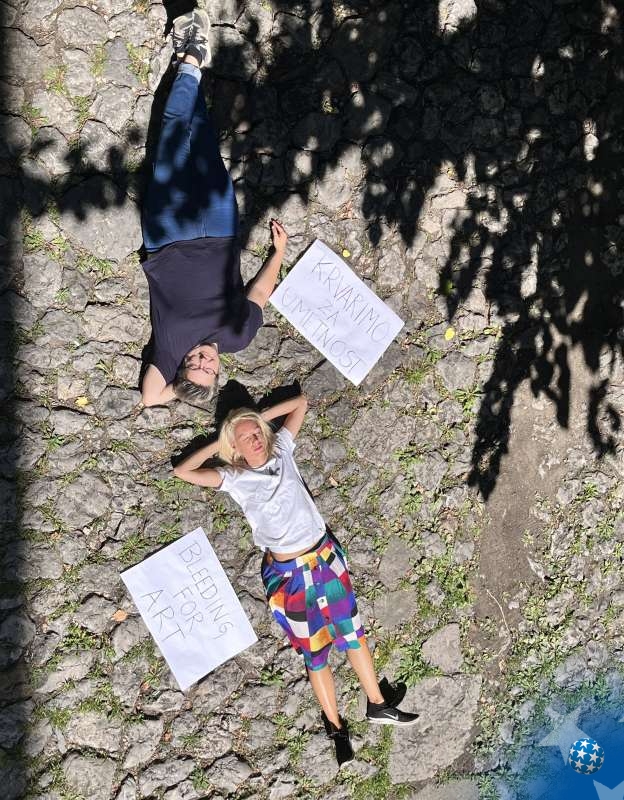

- You are the auteurs of the new project, A World Without Women. How did you come up with that title, and what made you tackle the issue of the structural inequality of women in Serbian theatre in this post-covid moment, and did that influence your decision to address this topic right now?

OLGA: What made us do it, as we state it in the performance, was one random listing of the titles included in the current repertories of several theatres, when we realized that, although it is well-masked through several strong authors who are present in repertories, the situation for women in Serbian theatres is rather grim. Then we decided to deal with various levels of that problem. One of those is the one of quantity, the fact that men are more often engaged as key authors. But we were also interested in other aspects of inequality in this area - the overlapping of gender and work, the situation with labor rights, the problem of structural violence, etc.

- How open were your female colleagues in Belgrade to share their experiences with you, and contribute to the research? Did your personal stories find their way in this project?

MAJA: Whenever we work on a project in which we also perform, we don’t opt for classical fictional characters because we are not classical actresses, but performers. Olga and Maja on stage are always some disjointed Olga and Maja who confront themselves with certain problems in an attempt of (self)critical observation of one’s own position in all of that. We are never simply the ones who live something, the ones who observe injustice; neoliberal capitalism always puts us in the position to also participate in it.

OLGA: As soon as we opened this topic, both in a formal way at a symposium, and in informal conversations with our female colleagues, it turned out that it was something that bothered the majority, but that there isn’t a platform from which that dissatisfaction could be articulated. Both our colleagues and we have experienced sexism, misogyny, discrimination, various forms of violence, and unequal salaries. We are also dissatisfied with the informal hierarchies that shape our professional and - doing what we do - also personal lives.

- Again, you tackle some touchy subjects, so I’m wondering if there was any form of censorship when you decided to turn some of the experiences into text?

MAJA: There was not any typical censorship or auto-censorship, but a decision to omit names and the recordings we had, especially of our conversations with the directors of theatres. Not because we were afraid to say something, we didn’t have any problem with that, but we have an ironical line in the performance: “We’re not interested in individuals but in the system”, which in a way is true. We wanted to point at clear systematic problems and structural violence which would not disappear if you simply brought another person on someone’s position. What we tried to point out was - as one of our colleagues said at the symposium - “the depth of patriarchal crisis”.

- You very often mention that it is a “class thing”. Could we say that theatre nowadays is also a class thing?

OLGA: It most definitely is and will become ever more so. Let’s start with education - the current trends indicate that drama studies will be affordable only to the rich, the ones who can pay tuitions, and living expenses during their studies. It means that the class rather than education will be what will determine if one can start practicing art. Practicing art is not paid enough, we are prone to self-exploitation, for the love of art, we accept unfavorable working conditions, in terms of time, nerves, and finances.

MAJA: At the same time, theatre very skillfully hides class positions, not only in terms of the position of artists, but also the structure of the employees and drastic class inequalities within theatres. Our institutional theatre functions according to “the show must go on” slogan, and all of us in the theatre hierarchy have internalized that. I’ve had this feeling for quite some time that everyone in theatre (not only in Serbia) finds the product (performances) more important than the people making them.

- What is the relation of power in Belgrade theatres now, and what is it like among the artists?

OLGA: Theatre is completely made of a complex power relations network. And it is very clearly set in terms of hierarchy. In one text, it is stated that artistic sphere can be observed like a pyramid, which is true. In order to have the so-called “great” artists, it is necessary to have many of those who do not belong to higher spheres, as well as many of invisible workers who serve the entire system. The situation is similar in football, which we refer to in the performance: on every great star there are thousands of those who have not managed to break through, behind every football team, there are the people trimming the grass, so they don’t break their legs. And I’d like to add: it has nothing to do with the alleged quality, because the process of the selection isn’t’ determined only by quality but by numerous other factors that have nothing to do with justice. The idea that the great ones will always manage to break through is an utterly internalized capitalist scam.

- In one interview, Maja said that it would be good to introduce a rule book into the law on theater. Do you have any idea what the rule book should look like, and what its three basic items would be?

MAJA: We tried to deal with that too, to see if we could make a model of author contract which would protect our rights both regarding the fees and regarding the violence in the workplace. If the rule book were ever to exist and to be obeyed, it would definitely have an item which would cover not only sexual harassment and violence but any form of abuse of power. Unfortunately, it is all so deeply ingrained into patriarchal structures that theatre too is based on, that it is all too theoretical for now, I’m afraid. We can only keep talking about it openly and apply some other forms of theatre togetherness in our processes.

- Have you discovered something that you never thought you would, or was everything as you expected?

OLGA: We entered the project aware of the structural violence, but the process revealed how deep it runs, and how unaware the very participants are. It was also interesting to see that violence in theatre has become normal, so no one notices it anymore, but romanticizes it by saying that it has to be that way, that it is the nature of passionate work, etc.

MAJA: On the other hand, what we find encouraging is that the conversations with colleagues made us realize that there are many of us who are dissatisfied with the system, aware of the violence and the inequality that get reproduced both on the level of work and on the level of representation.

- The finances reduced your research to Belgrade, although I don’t think the situation could be any better in other towns. How likely is it for the performance to be played out of Belgrade and to initiate a dialogue?

MAJA: We are hoping to take the performance to as many places as possible. As for the dialogue, we’ll see. I think that it is important for it to be opened on the state level. I’d like to believe that our theatre is capable for a round of true self-scrutiny, that more people who are dissatisfied with the working conditions will demand for the things we talk about to change.

- Olga, your play The Folk Play is about lesbian relationship between the protagonists. Texts that tackle those issues are very rare. Are there many queer workers in theatres, are they accepted by their colleagues, and are their narratives present on Belgrade scenes? For example, in the USA, most LGBT+ actresses would be chosen to present their community, female directors will direct the plays dealing with that topic, they would be surrounded by a team from the same community, while here people don’t seem to think about it at all. Why do you think that is the case?

OLGA: First, we cannot compare our context with the American all that easily. The number of outed people here is insignificant and that won’t change any time soon. Unlike the USA, the policies of identity in our context, except in activism, where they are almost the only, and most definitely the most visible approach, haven’t become normal in other parts of life. It can be linked to the homophobic surrounding, but also to the fact that uncritical and literal transliteration of American concepts to our context cannot function all that easily. On the other hand, many people would call “political correctness” if we mentioned this. Woke culture has many flaws, but the problem here is that I still haven’t heard someone oppose political correctness unless trying to justify their own sexism, homophobia or racism, or simple rudeness. There is nothing “correct” about people insisting to speak. The one who has the power to make a narrative has the power to shape our understanding of reality, of politics and of the relation of power within it. That is why we insist, from the point of view of any minority (class, gender, race…) that we can only speak for ourselves. The problem is that privileged people often use the story from minorities in order to prove their (political and/or aesthetical) point. Then it becomes instrumentalization and awfully irritating and wrong. That is where the wish and struggle of the minorities to speak for themselves come from.

- It's very important to mention that you, Maja, have never refrained to be a performer or a director. That motivated me to try other things except acting. The same applies to you, Olga. How do you prepare for performances? How do you feel on stage, and where is the connection between Maja/Olga dramaturge and Maja/Olga actress, performer? Do you have stage fright and how do you deal with it? Do you like improvising?

MAJA: A multilayered dance takes place between Olga and Maja/artists and Olga and Maja/friends. I think none of this would be the same if we weren’t friends. I was thinking, and I believe Olga will agree, that two of us are antipodes on so many levels - physical, personality, performing… But when it comes to poetics, we are always on the same page. No matter how many conflicts we might have during the process, I can’t remember ever having any problems about some crucial questions in terms of ideology. We normally prepare by asking ourselves in the backstage: “Why are we doing this (again), why don’t we just stick to writing?” We do have stage fright, of course, but being together on stage means a lot. We even learned how to help each other out in some critical situations when things go wrong.

- Dear Maja and Olga, thank you for this inspirational interview.